home |

EXPOSITION 1867 Paris

![]()

![]()

5 facteurs de pianos avec la médaille d'or : CHICKERING, Philippe-Henry HERZ Neveu (°1863), STEINWAY & STREICHER

"Les fabricants de pianos de toute l'Europe et de l'Amérique qui ont

envoyé leurs produits à l'Exposition universelle sont au nombre de

cent cinquante-huit.

1.

STEINWAY

NOTICE OF THE PIANOS EXHIBITED FROM THE UNITED STATES.

Until the third decade of the present century only European instruments found a ready market in America. It was soon found, however, that no wooden framed piano could long resist the extraordinary climatic changes of the country without requiring almost constant tuning and repairs. In the Exhibition of 1867, two firms more especially dispute the palm of pre-eminence — Messrs. STEINWAY & Sons, of New York, and Messrs. CHICKERING & Sons, of New York and Boston. The jury readily acknowledged the remarkable qualities of the pianos of these two houses, and, pronouncing them both first-class products, gave equal awards to each, and the highest in its gift, viz: the gold medal. By a decree of the Emperor Mr. C. F. CHICKERING was created Chevalier of the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honor of France. Each of these firms has, from time to time, taken out patentsfor improvements. Mr. CHICKERING claims to be the sole inventor of the circular scale, and to have made many other improvements which have been rendered necessary from time to time by the development of musical science. Messrs. STEINWAY & Sons claim the application of various important improvements necessary for avoiding the thin and disagreeably nasal character of tone at first possessed by the iron frame, and for supplying that solidity of construction which the gradual extension of the musical capabilities of the piano rendered necessary. They claim also the introduction of over-stringing as well as the adoption of agraffes. It will not be presumed in this notice to judge of the respective merits of the improvements or the claims as to priority of the inventions of either party, or to attempt a technical particularization of them, but it may be said that the pianos of Messrs. CHICKERING & Sons and of Messrs. STEINWAY & Sons, not forgetting the beautiful cycloid instrument manufactured and exhibited by Messrs. Lindemann & Sons, are unrivalled, and that while these instruments have a solidity of construction which withstands the deleterious influence of any climate, their depth, volume, power and delicacy of tone are fully equal to all that can be required. Reports of the United States Commissioners to the Paris Universal ..., Volume 2, William Phipps Blake, 1870, p. 261-262

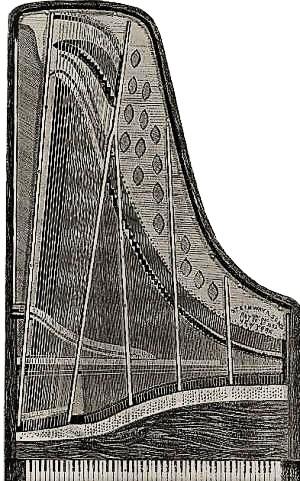

Messrs. STEINWAY have taken out various patents for inventions, new grand piano actions, &c.; but the improvement on which they lay the greatest stress was patented by them in December 1859. It consisted (I will use their own words) "of the introduction of a complete cast-iron frame, the projection for the agraffes lapping over and abutting against the wrest plank, together with an entirely new arrangement of the strings and braces of this iron frame, by which the most important and advantageous results were achieved. The strings were arranged in such a position that in the treble register their direction remained parallel with the blow of the hammers, whilst from the centre of the scale the unisons of the strings were gradually spread from right to left in the form of a fan, along the bridge of the sounding board, the covered strings of the lower octaves being laid a little higher and crossing the other ones (in the same manner as the other strings), and spread from left to right on a lengthened sound-board bass bridge, which ran in a parallel direction to the first bridge. By this arrangement several importaut advantages were obtained; by the longer bridges of the sounding-board a greater portion of its surface was covered; the space between the unisons of the strings was increased, by which means the sound was more powerfully developed from the sounding-board, the bridges being moved from the iron-covered edges nearer to the middle of the sounding-board, producing a larger volume of tone, whilst the oblique position of these strings to the blow of the hammers resulted in obtaining those rotating viurations which gave to the thicker strings a softness and pliability never previously known." The instruments exhibited by Messrs. STEINWAY consist of two concert grands, a parlour grand, a square, and an upright. With regard to the grand pianos, I can only say that the specimens now placed before the public are, in my opinion, as fine as pianos can be. Every attribute of a splendid instrument is here; strength, depth, sonority, brilliancy, facility of touch, and excellence of construction, combine to make Messrs. STEINWAY's concert-grand a piano of the very first excellence. His other instruments are every bit as remarkable, and I should say that such a square piano was never heard before; if such instruments are frequently turned out in the States I can readily understand that their vogue should continue. The price of the first grand, as also Messrs. CHICKERING's best piano, is 300/.; they are cased in rosewood, and, by comparing them with instruments of similar calibre made by European manufacturers, it will be seen that the American pianos are the more expensive. The square piano to which I have alluded cost 180/., but I am bound to say that, having regard to the rare excellence of the instruments, I consider them worth their money." Reports on the Paris Universal Exhibition, 1867, Volume 2, p. 203-205

MANUFACTURE OF PIANOS IN THE UNITED STATES. He began by bringing together and under his personal supervision the various processes of fabrication for all parts of the instrument, from keys to case. In 1837 he engaged the services of Alpheus Babcock.

Babcock was the inventor of the entire cast-iron frame, the

fourth and final system of bracing, the greatest improvement

recorded in the history of the piano, certainly since 1824, not to

assume an earlier date. It was applied with the most satisfactory

results to square pianos by Swift & Wilson, of Philadelphia, with

whom Babcock was associated; but it was not until he entered the

establishment of CHICKERING that it received its last modifications

and was adapted to the grand and upright piano. In 1855, Messrs. STEINWAY & Sons, of New York,

made a piano with a solid front bar and a full iron frame, and with

the wrestplank bridge made of wood. "the secret of the great tone of the American pianos consists in the solidity of the construction, which is found as well in the square piano as in the grand piano. The instrument which was and still continues in general use in America is the square piano, which has almost disappeared from European manufacture. The principle of solidity of the American pianos is found in the iron frame, east in one solid piece, which resists the tension of the strings instead of the wooden framework of the European pianos." After noticing, the invention by Babcock, and the exhibition made by Meyer, in 1833, he says : "The first who thought of employing these frames for the solidity of the instruments was a manufacturer of Philadelphia, named Babcock; he finished the first instrument of this kind in 1825." In 1833, Conrad Meyer, another maker, of the same city, exhibited at the Franklin Institute a piano with an entire cast-iron frame. These manufacturers did not understand the advantages of their innovation; these instruments being strung with strings too thin and not in equilibrium with the metallic frame, their tone was thin and had a metallic sound. In 1840, Jonas CHICKERING, of Boston, founder of the family of piano-makers of that name, took a patent for an iron wrestplank bridge with a projection (socket-rail,) both being cast with the frame in one solid piece. He commenced to use heavier strings on this apparatus, the sonority of which was found to be better. As is always the ease, this invention was improved by degrees. To day the strings of the American pianos are a great deal heavier than those used by the French, German, and English makers.

To place them into vibration, the hammers required a more energetic

attack than in the English and French actions; hence the

considerable increase of the strength of tone. But this advantage is

balanced by the hardness of attack which renders the blow of the

hammer too perceptible, an objection more offensive in the grand

than in the square piano. The strings were arranged in such a position, that in the treble register their direction remained parallel with the blow of the hammers, whilst from the centre of the scale the unisons of the strings were gradually ipread from right to left in the form of a fan, along the bridge of the sound-board — the covered strings of the lower octaves being laid a little higher and crossing the other ones (in he same manner as the other strings,) and spread from left to right on a lengthened soundboard bass bridge which ran in a parallel direction to the first bridge. By this arrangement

everal important advantages were obtained; by the longer bridges of

the sounding-board a reater portion of its surface was covered; the

space between the uuisons of the strings as increased, by which

means the sound was more powerfully developed from the sounding

on the bridges, being moved from the iron-covered edges, nearer to

the middle of the junding-board, producing a larger volume of tone, whilst the

oblique position of these rings to the blow of the hammers resulted is obtaining

those rotating vibrations, which live to the thicker strings a softness and

pliability never previously known. The new system of bracing was also far more

effective, and the power of standing in tune greatly ineased. In the middle the

strings were placed in the shape of a fan, from right to left, as

far as the space permitted. The bass strings, spun upon steel wires,

were placed from left to right above the others, upon a higher

bridge placed belaud the first. The advantages of this system are as

follows: In no branch of industry did the United States win more distinction at the Universal Exposition of 1867 than in the manufacture of pianofortes. The splendid specimens exhibited by the two firms that have been mentioned, Messrs. STEINWAY & Sons, of New York, and Messrs. CHICKERING, of Boston, created a profound sensation not only with artists and professional musicians, but also with the musical public at large. Both firms exhibited grand, square, and upright pianos, and each received a gold medal upon the award of the international jury. The award of two gold medals to piano

manufacturers in the United States is the more significant and

gratifying, when it is considered that the jury on musical

instruments awarded but four gold medals, and that no member of this

jury was from the United States. Brilliant in the treble, singing in the middle, and formidable in the bass, this sonority acts with irresistible power on the organs of hearing. In regard to expression, delicate shading, and variety of accentuation, the instruments of Messrs. STEINWAY have over those of Messrs. CHICKERING an advantage which cannot be contested. The blow of the hammer is heard much less, and the pianist feels under his hands a pliant and easy action which permits him at will to be powerful or light, vehement or graceful. These pianos are at the

same time the instrument of the virtuoso who wishes to astonish by

the eclat of his execution, and of the artist, who applies his

talent to the music of thought and sentiment bequeathed to us by the

illustrious masters; in a word, they are at the same time the pianos

for the concert room, and the parlor, possessing an unexceptional

sonority."

It seems to us—and the opinion of celebrated experts coincides with

ours on this point—that it is useless to have recourse to the

contrivance of overstringing where there is sufficient space for a

parallel distribution of the strings. The reasons for preferring the

parallel system are based on the laws of acoustics, and confirmed by

the direct testimony of scientific experience.

It was invented and

patented in France by Pape, in 1828; and its practical application

to an upright and to a grand piano by Cadby was exhibited at London

in 1851. It has long since been renounced both by Pape and Cadby.

They found that this plan of attaching more or less firmly to the

instrument its most vital part, the sounding board, could not be

made to co-exist with the requisite solidity of construction.

Dans le dessus du piano, on continua de placer les cordes parallèlement à la direction des marteaux, parce qu'il avait été reconnu, dans le piano carré, que cette position des cordes produit des sons plus intenses dans cette partie de l'instrument.

Dans le médium, les cordes furent tendues en forme d'éventail, de

droite à gauche, autant que l'espace le permettait. Les cordes de la basse,

filées sur acier, furent tendues de gauche à droite, au-dessus des autres, sur

un chevalet plus élevé et placé derrière le premier. 1° La longueur des chevalets de la table d'harmonie est augmentée, et l'on peut profiter de grands espaces qui n'avaient pas été utilisés jusque-là;. 2° l'espace d'une corde à l'autre est agrandi, d'où il suit que leur résonnance se développe plus puissamment et plus librement;

3° les chevalets, posés plus au centre de la table d'harmonie, et

conséquemment plus éloignés des bords ferrés de la caisse, agissent avec plus

d'énergie sur l'élasticité de cette table, et favorisent la puissance du son; de

plus, en gardant les mêmes dimensions pour l'instrument, la longueur des cordes

se trouve augmentée; 4° la position des cordes du médium et de la basse, vers la

direction du coup de marteau, produit des vibrations circulaires, d'où résultent

des sons moelleux et purs. Ces améliorations consistent en un double

cadre en fer, avec plaque d'attache et barrages, fondus en une seule pièce. Le

côté gauche de ce cadre reste ouvert, et par cette ouverture se glisse la table

d'harmonie: à celle-ci s'adapte un appareil spécial, lequel consiste en un

certain nombre de vis qui servent à comprimer ses bords à volonté. Les pianos de MM. STEINWAY père et fils sont également doués de la splendide sonorité des instruments de leur concurrent; ils ont aussi l'ampleur saisissante et le volume, auparavant inconnu, d'un son qui remplit l'espace. Brillante dans les dessus, chantante dans le médium, et formidable dans la basse, cette sonorité agit avec une puissance irrésistible sur l'organe de l'ouïe. Au point de vue de l'expression, des nuances délicates et de la variété des accents, les instruments de MM. STEINWAY ont sur ceux de MM. CHICKERING un avantage qui ne peut être contesté; on y entend beaucoup moins le coup de marteau, et le pianiste sent sous sa main un mécanisme souple et facile, qui lui permet d'être à volonté puissant ou léger, véhément ou gracieux. Ces pianos sont à la fois l'instrument du virtuose qui veut frapper par l'éclat de son exécution, et celui de l'artiste qui applique son talent à la musique de pensée et de sentiment que nous ont laissée les maîtres illustres; en un mot, ils sont en même temps des pianos de concert et de salon, doués d'une sonorité exceptionnelle. [...] Il n'y eut pas autant d'indifférence à l'Exposition internationale de Londres (1862), où MM. STEINWAY père et fils avaient envoyé plusieurs instruments, parmi lesquels se trouvait un grand piano de concert. Un des fils de M. STEINWAY avait accompagné ces instruments à l'Exposition; il les fit jouer incessamment, et le public, charmé par leur grand son, ne cessa de s'amasser en foule pendant plusieurs mois dans le compartiment qui les contenait. Le Jury ne fut pas moins intéressé que le public parla puissance etle charme de ces pianos, particulièrement par le piano carré, égal en sonorité aux plus beaux pianos à queue. Il a été rendu compte alors dans la Gazelle musicale de Paris (quatrième lettre sur les instruments de l'Exposition internationale de Londres) de l'effet produit par ces pianos. La récompense unique de cette Exposition fut décernée à MM. STEINWAY." Exposition universelle de 1867: Rapports du jury international, Volume 2, 1868, Fétis, p. 255-262

CHICKERING

The first in the field was the late Mr. Jonas CHICKERING, of Boston. His pianos appear to have been modelled on those of Erard, of Paris, but were constructed with the full iron frame. The line of the wrest plank bridge consisted of an iron ledge projecting upwards from the iron frame. Into this ledge holes were drilled, which were lined with cloth; and through these the strings were laid. Mr. CHICKERING took out a patent for this upward projecting ledge in 1843. It is interesting to trace the steady yet rapid progress which has been made in the manufacture of American pianos, but, having regard to the space at my disposal, I fear I must pass over the intermediate improvements effected by Messrs. CHICKERING, and come at once to the superb instruments which are now standing in their name at the Exhibition. It is impossible to speak too highly of these pianos; whether it be in tone, or touch, or general appearance, and construction, it is alike difficult to find anything to criticise. Having said thus much, I think I need say no more." Reports on the Paris Universal Exhibition, 1867, Volume 2, p. 203-205

Nearer by, it must be added, there is combined with this powerful tone the impression of the blow of the hammer, which produces a nervous sensation by its frequent repetition. These orchestral pianos are adapted to concerts; but in the parlor, and principally in applying them to the music of the great masters, there is wanting, by the same effect of the too perceptible blow of the hammer, the charm that this kind of music requires. There is something to be done here, to which the reporter must call the attention of the intelligent manufacturer of these grand instruments, without in other respects wishing to diminish their merits." Reports of the United States Commissioners to the Paris Universal Exposition ..., William Blake, 1870, p. 80-85

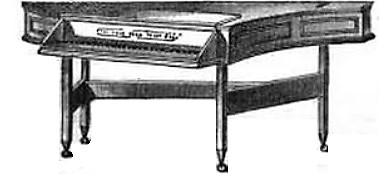

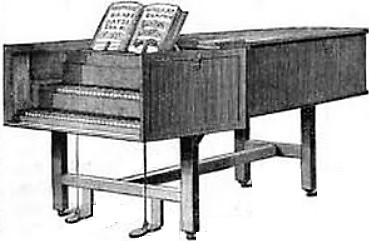

Great, however, as is the commercial and industrial importance of this manufacture. it is infinitely less than the social importance of the piano. Of its influence upon society Thalberg, the greatest pianist of the past age, says, in the official report of the jury on musical instruments at the " World’s Fair,” London, 1851 : — One of the most marked changes in the habits of society, as civilization advances, is with respect to the character of its amusements. Formerly, nearly all such amusements were away from home, and in public ; now, with the more educated portion of society, the greater part is at home and within the family circle, music on the piano contributing the principal portion of it. In the more fashionable circles of cities, private concerts increase year by year, and in them the piano is the principal feature. Many a man engaged in commercial and other active pursuits finds the chief charm of his drawingroom in the intellectual enjoyment afforded by the piano. By its use many persons who never visit the opera or concerts become thoroughly acquainted with the choicest dramatic and orchestral compositions ; this influence of the piano is not confined to them, but extends to all classes ; and while considerable towns have often no orchestras, families possess the best possible substitute, making them familiar with the finest compositions. The study of such compositions, and the application necessary for their proper execution may be, and ought to be, made the means of greatly improving the general educational habits and tastes of piano students, and thus exerting an elevating influence in addition to that refined and elegant pleasure which it directly dispenses." The exact date of the birth or invention of the piano-forte is involved in as much obscurity as its country. Germans, French, and English all lay claim to the invention during the second decade of the past century; but it seems most probable that the honor should be awarded to an Italian, Bartolomeo Cristofali, of Padua, to whom it is ascribed in the Giornale d’ltalia for the year 1711. Stringed instruments of the same general character, viz. : the clavichord, spinet, and harsichord, had, howevar, been made for nearly two hundred years before. In the clavichord the strings were struck or pressed by pieces of wire attached to the keys. In the spinet the string was struck in a manner to imitate the action of the human fingers on the strings of the harp, by pieces of crow or raven quill attached to. the tongue of a little instrument termed a “jack,” at' tached to the finger-key.

Fig. 1 is a representation one of these inflimmeuts now in the possession of Messrs. CHICKERING & Sons, of Boston. The spinet had but a single string to each note. When two strings came to be used to each note, the name of the instrument was changed to that of the harpsichord, or horizontal harp. The strings were still vibrated by means of quills, although from the rapid wear, and the long time occupied in frequent “requilling” the instrument, other elastic substances, as ivory and leather, were substituted, but the instrument is said to have lost in sweetness by the change. Messrs. CHICKERING & Sons have in their possession one of these instruments with two rows of keys, of which Fig. 2 is a representation.

The great step made in the improvement of instruments of this class, and which gave birth to the piano-forte, was the substitution of hammers to strike directly against the string for the devices previously used for pulling it or striking it with a glancing action. It is stated, however, by writers of the period, that the touch and mechanism of the earlier pianos were so imperfect that no quick music could be played upon them, but that in slow music the effect was very fine. So far from there being any such defect in the pianos of the present day, there is no instrument of which the touch is so delicate, or by which the most complicatedmusic can be played with such brilliancy and rapidity of execution. We believe that the first piano-forte ever manufactured in this country was manufactured in New York, near the close of the last century, by a Mr. Geib, a German, who had previously been engaged in the business in London ; but so lately as the year 1823, when the late Mr. Jonas CHICKERING established his business in Boston, the number of pianofortes made in this country was very small, most of the instruments then used being imported from England. This gentleman, originally a cabinet-maker, brought into the business great mechanical skill and scientific powars, exquisite musical taste and an undaunted will, and the result has been that the establishment now carried on by his three sons as the firm of CHICKERING & Sons, in Tremont street, is the most extensive piano manufactory in the world, and during the year 1865 the piano trade of the United States amounted to fifty-nine millions, two hundred and eighty-four thousand, six hundred and seventythree dollars ($59,284,673), and the number of pianos made was upwards of one hundred and eighteen thousand, or a little over three hundred and eightyone for every working day in the year. Mr. Jonas CHICKERING and his successors, Messrs. CHICKERING & Sons, have made altogether, to the first of the present month, no less than thirty thousand five hundred instruments, and the firm now turn out forty per week. Their instruments haVe long hada world wide reputation, and so far from there being now any importation of pianos to this country, they are now exported to Europe. One of the greatest improvements ever made in the pianoforte was the full iron frame, and the credit of this is due to Mr. Jonas CHICKERING, who introduced it as early as the year 1838. This added immensely to the solidity of the instrument, the permanence and purity of the tone, and the re; sources of the key-board through added strings, and is used in all the best pianos now made in this country. Mr. CHICKERING was also the sole inventor of the circular scale—now so generally used by manufacturers in this country and in Europe. It was first used (or published) Nov. 29, 1845. It was not patented—the inventor preferring to regard it as. one of the things which all should use. The improvements which Mr. CHICKERING made in the entire construction of the instrument were r. merous. His whole mind was absorbed in the idea" of a perfect piano ; to obtain such a desideratum he labored, experimented, sought advice and assistance, and left no means untried which could aid in his endeavor.

Messrs. CHICKERING & Sons manufacture pianos of the three classes known as “grand," “square,” and “upright,” and of each class several different kinds, making in all twenty-one different styles, at prices generally varying from $350 to $1,500; but they are now making six instruments worth $2,500 each. “'hile 0n the subject of style we may remark on the extreme artistic beauty of the exterior of the modern piano-fortes, and in illustration of this We give a representation (see figure above) of one of Messrs. CHICKERING & Son's square pianos, that the reader may compare it with the kitchen-table-like style of the antiquated spinet and harpsichord. The factory of Messrs. CHICKERING & Sons, situated on the westerly side of Tremont street (between Camden and Northampton streets), Boston, is said to be the largest building in the United States, except the National Capitol and the Patent Office at Washington. It occupies a hollow square of about five acres of ground, is five and six stories, and contains eighteen acres of floor. It is lighted by day through 900 windows and at night by 600 gas lights, and contains fifteen miles of steam pipe for heating. The extensive machinery is driven by an upright beam engine of 125 horse-power, built by Otis Tufts, of East Boston, and nearly 400 men are employed. This building was commenced on June 15, 1853, and went into operation June 1, 1855. Its capacity is sufficient to enable the firm to turn out one hundred pianos per week." American Artisan and Illustrated Journal of Popular Science, 1867, p. 244

A cette Exposition, Pierre Erard avait fait des efforts extraordinaires pour triompher de tous ses concurrents, et rien n'avait été négligé pour absorber sur ses instruments l'attention générale et assurer le succès qu'il ambitionnait. L'instrument de M. CHICKERING ne produisit pas alors l'effet qu'il méritait, comme en jugea alors celui qui écrit ce rapport. Pendant et après l'Exposition, on ne parla pas du piano américain. Soit qu'ils eussent été mécontents du résultat obtenu par eux à Londres, soit que leur attention fût détournée par quelque intérêt plus important, MM. CHICKERING n'envoyèrent pas de piano à l'Exposition universelle de Paris, en 1855; maison y vit un piano carré de très-grande dimension, sous le nom de M. Ladd, de Boston. Cet instrument à cordes croisées et à double table d'harmonie

était remarquable par la puissance et l'égalité des sons; mais sa forme, qui

n'était plus de mode, fut cause qu'on ne lui prê,ta pas non plus l'attention

qu'il méritait. D'ailleurs, personne ne le jouait; il resta oublié, sauf du

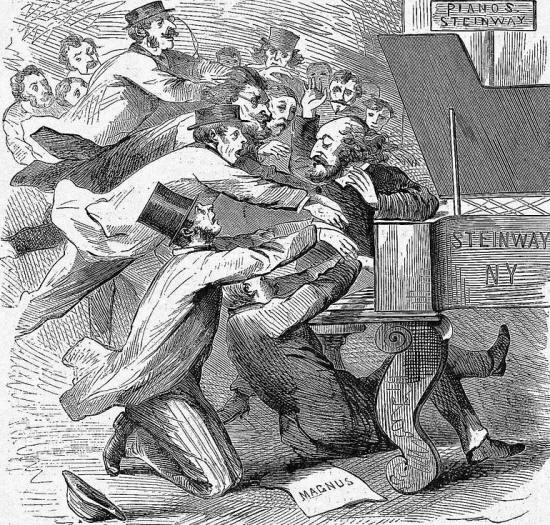

rapporteur de l'Exposition, qui mentionna ses qualités. [...] A ces noms s'ajoutèrent ensuite ceux de Léopold de Meyer, d'Alfred Jael, de Benedict, de Mme Arabella Goddard, de Moscheles, de Balfe et de beaucoup d'autres. La lutte entre les deux plus grands établissements de fabrication de pianos américains, à savoir de MM. STEINWAY et CHICKERING, s'est produite avec un caractère fiévreux dans l'Exposition universelle actuelle de Paris : elle n'a pas eu toujours la dignité convenable; on a usé et abusé des réclames de journaux; mais on ne peut méconnaître le vif intérêt qu'a pris à cette lutte la foule prodigieuse qui n'a cessé de se réunir autour de ces instruments lorsquon y jouait. Évidemment, il y avait là quelque chose de nouveau qui impressionnait le public; ce nouveau était une puissance de son auparavant inconnue. Ce n'est pas à dire que ce son formidable ne rencontrât que des éloges; les partisans dela facture européenne des pianos reprochaient aux Américains de lui avoir sacrifié toutes les autres nécessités de l'art : le moelleux, les nuances délicates et la clarté. D'autres disaient que ce grand son non seulement n'est pas

nécessaire pour exécuter la musique de Mozart, de Beethoven et d'autres maîtres

du premier ordre, mais qu'il y serait nuisible. On peut répondre à ces amateurs

de la musique classique par ces paroles du rapporteur de la classe des

instruments de musique à l'Exposition de 1855 : L'art, la mu« sique surtout, se transforme à de certaines

époques et veut « des moyens d'effet conformes à son but actuel: or, le déve«

loppement de la puissance sonore est la tendance donnée à «l'art depuis le

commencement du xixe siècle. La facture du piano a suivi cette tendance,

particulièrement le piano de « concert, qui doit souvent lutter avec des

orchestres consi« dérables,et dont les sons doivent se propager dans de vastes «

salles.» Ce problème, le fait vient de prouver qu'il a été résolu en Amérique. Le rapporteur ne croit pas devoir traiter ici les questions de priorité et de propriété d'invention, parce que ces questions sont souvent obscures et peuvent toujours entraîner de longues discussions. En voyant les mêmes moyens mis en œuvre librement par

plusieurs fabricants de pianos dans le même pays, il en conclut que ces choses y

sont dans le domaine public, et son attention n'est fixée que sur le mérite de

l'exécution et sur les résultats. L'instrument dont l'usage était et est encore le plus général en Amérique est le piano carré, lequel a à peu près disparu de la fabrication européenne. Le principe de solidité des pianos américains se trouve dans un cadre en fer fondu d'une seule pièce, sur lequel s'opère la traction des cordes, au lieu de la charpente en bois des pianos européens. Le premier qui imagina d'employer ces cadres pour la solidité des instruments fut un facteur de Philadelphie, nommé Babcock; il termina son premier instrument de ce genre en 1825. En 1833, Conrad Meyer, autre facteur de la même ville, exposa

à l'Institut Franklin un piano avec un cadre complet en fer fondu. Ces

industriels n'avaient pas compris les avantages de leur innovation, car leurs

instruments étaient montés en cordes trop minces, qui n'étaient pas en rapport

d'équilibre avec le cadre métallique; leur son était maigre et sentait

la/erraille. Pour les mettre en vibration complète, les marteaux doivent

avoir une attaque plus énergique que dans le mécanisme anglais et français; de

là l'augmentation considérable de la force des sons; mais cet avantage est

balancé par la dureté de l'attaque, qui rend le coup du marteau trop sensible;

inconvénient plus choquant encore dans le piano à queue que dans le piano carré.

[...] De près, il faut bien le dire, à ce son puissant se joint l'impression du coup de marteau, qui finit par produire une sensation nerveuse par sa fréquente répétition. Ces pianos orchestres conviennent aux concerts; mais, dans le salon, et surtout en les appliquant à la musique des grands maîtres, il y manquerait, par l'effet même de ce coup de marteau trop prononcé, le charme que requiert ce genre de musique. Il y a là quelque chose à faire, sur quoi le rapporteur croit devoir appeler l'attention de l'intelligent fabricant de ces grandioses instruments, sans toutefois diminuer leur mérite dans le reste." Exposition universelle de 1867: Rapports du jury international, Volume 2, 1868, Fétis, p. 255-262

Pianoforti quadrati - [...] Fra i quadrati, ossian pianoforti a tavola, stanno in prima linea uno della fabbrica Chickering di Boston, e quello esposto dalla firma Steinway di Nuova York, per la maggior loro sonorità. Questi bellissimi strumenti sorpassavano diversi pianoforti a coda per la possanza e la bella qualità dei bassi e dei medii. Gli acuti davano una voce chiara, cristallina, e l'assieme era soddisfacentissimo nel suo genere. [...] Pianoforti verticali. - [...] Chickering anche aveva un buon verticale di noce di bella voce e buona tastiera." Il Pianoforte, guida pratica per costruttori, accordatori, etc., Sievers, 1868, p. 214/223/226

HERZ Phillippe à Paris

Henri HERZ

Ces éléments constitutifs des instruments recherchés par les pianistes sont tout à fait développés dans le piano à queue qu'il a exposé, et qui, de plus, est d'une forme très-élégante. Le jeune facteur savait bien qu'un débutant n'a pas à se préoccuper des séductions de l'enveloppe pour présenter ses produits, qui doivent s'adresser aux oreilles bien plus qu'à la vue. Mais il a tenu commpte d'une vérité proclamée par la sagesse des nations, et qui peut s'appliquer à tout : il en a changé la lettre et suivi l'esprit, convaincu que si le luxe estérieur ne fait pas le piano, du moins il le pare. M. Philippe HERZ a placé un mécanisme très-soigné sans une belle caisse d'ébène, avec inscrustations et ornements dorés du style Louis XIV. Pour la valeur artistique de cet instrument, on a pu en juger lorsqu'une de nos célèbres artistes, Mme Escudier-Kastner, l'a fait si bien valoir en ecécutant une fantaisie de Thalberg, un fragment de Mozart et le Torrent, de Lacombe.

En faisant

l'éloge de cette manufacture, on ne doit pas oublier l'habile

coopérateur, dont M. Philippe HERZ s'est assuré le concours, M.

Marcus KNUST,

qui a travaillé, comme contre-maître, six ans chez

ERARD,

douze chez PLEYEL,

et dix-huit ans chez Henri HERZ, et qui a été initié ainsi aux procédés

des meilleures écoles de facture."

AMÉDÉE MÉREAUX.

26.04.1868 - Voir

La médaille d'or, la seule pour la France, lui avait été décernée par le jury international à la majorité de 14 voix sur 15 membres présents. Il est vrai d'ajouter que, par suit d'une erreur, le nom de M. P . HERZ neveu et Cie ne figurait pas sur le premier tirage du catalogue des recomponses, et que cet oublie e'tait dû à un malentendu on ne peut plus regrettable, suscité d'ailleurs par les jalousies rivales, disons le mot.

Nous apprenons avec grande satisfaction que les difficultés avec la

Commission impériale sont entièrement aplanies, et que la médaille

d'or, ainsi que le diplôme qui l'accompagne, vient d'être délivrée à

MM. Philippe, H. HERZ neveu et Cie.

Et pour leurs coups d'essai veulent des [c]oups de maitre.»

Ces éléments constitutifs des instruments recherchés par les pianistes sont tout à fait développés dans le piano a queue qu'il a exposé, et qui, de plus, est d'une forme très-élégante. Le jeune facteur savait bien qu'un débutant n'a pas à se préoccuper des séductions de l'enveloppe pour présenter ses produits, qui doivent s'adresser aux oreilles bien plus qu'à la vue. Mais il a tenu compte d'une vérité proclamée par la sagesse des nations, et qui peut s'appliquer à tout il en a changé la lettre et suivi l'esprit, convaincu que si le luxe extérieur ne fait pas le piano, du moins il le pare. M. Philippe HERZ a placé un mécanisme très-soigné dans une belle caisse d'ébène, avec incrustations et ornements dorés du style Louis XIV.

Pour la valeur artistique de cet instrument, on a pu est juger

lorsqu'une de nos célèbres artistes, Mme Escudier-Kastner, l'a fait

si bien valoir en exécutant une fantaisie de Thalberg, un fragment

de Mozart et le Torrent, de Lacombe.

La Presse de Paris tout entière a sanctionné par ses éloges la décision rendue par la commission impériale en faveur de cette maison, placée, dès aujourd'hui, à la tête de la fabrication de Pianos en Europe." Journal du Loiret, 26/06/1868, p. 3 (Aurelia.Orleans.fr)

Paris, le 15 juillet, 1868. Je vous demande la permission de vous rappeler que notre maison est la seule maison française qui ait obtenu la médaille d'or à l'Exposition universelle du 1867 pour la fabrication des pianos.

L'omission de notre nom dans la première édition du catalogue

officiel est le résultat d'un malentendu, et va être réparée.

Veuillez agréer, Monsieur, nos salutation les plus sincères,

Le succès sans précédent que cette jeune maison (fondée seulement

depuis quatre années) a obtenu à l'Exposition universelle, d'une

façon si éclatante, comme on se le rapelle (puisque le jury

international a voté à M. Philippe H. HERZ neveu cette médaille d'or

à la majorité de 14 voix sur 15 membres), ce succès, disons-nous,

n'est que la juste récompense des efforts incessants que cette

manufacture a faits et des progrès qu'elle a réalisés depuis sa

fondation, sans jamais s'arrêter un seul instant. C'est, en effet, la seule médaille d'or décernée à la France pour la fabrication des pianos. Le triomphe n'en est donc que plus ccomplet." M.E. 26.07.1868

«A propos d'art et de concerts, je rappelle ici avec plaisir que la commission impériale de l'Exposition universelle de 1867 a donné une éclatante satisfaction à M. Philippe H. HERZ neveu, en réparant l'oubli dont ce célèbre facteur a été victime. Le Moniteur a constate que, par erreur, la maison Philippe H. HERZ neveu, fondée en 1863, ne figure pas au catalogue officiel des récompenses décernées à l'industrie des pianos à l'Exposition unniverselle de 1867. En effet, le jury international lui a vote, par 14 voix sur 15, une médaile d'or, la seule qui ait été obtenue par un fabricant français." La Presse, 27/11/1868, p. 2-3 (gallica.bnf.fr)

L'émission commise dans le catalogue officiel de l'Exposition 1867, au préjudice de la maison Philippe H. HERZ, neveu et Cie, constatait que cette jeune maison était la seule, en France, qui ait obtenu la médaille d'or pour la perfection et la supériorité de ses instruments. A l'époque de l'inauguration des salons de la rue Scribe, en 1864, la presse avait été unanime à reconnaître, avec tous les artistes, les progrès énormes que le chef de cette nouvelle maison venait de réaliser dans la fabrication des pianos, et l'admiration provoquée alors par les nouveaux instruments faisait facilement prévoir la victoire remportée à l'Exposition de 1867. Dans cette industrie de la fabrication des pianos qui a pris tant d'extension depuis quelques années, cinq médailles d'or seulement ont été accordées par le jury international deux la facture américaine, une à l'Autriche, une à l'Angleterre, une, enfin, à la facture française, décernée à M. Philippe-HERZ Neveu et Cie." Le Figaro, 08/12/1868, p. 3 (gallica.bnf.fr)

A l'époque de l'inauguration des salons de la

rue Scribe, en 1864, la presse avait été unanime à reconnaître, avec

tous les artistes, les progrès énormes que le chef de cette nouvelle

maison. venait de réaliser dans la fabrication des pianos, et

l'admiration provoquée alors parles nouveaux instruments faisait

facilement prévoir la victoire remportée à l'Exposition de 1867.

Un article du journal La

France nous apprend qu'il vient de s'opérer une remarquable

transformation dans la fabrication des pianos à queue de cette

manufacture.

On se rappelle le bruit qui

s'est fait autour des pianos américains : une jeune maison de Paris

a pu seule lutter et remporter une victoire éclatante dans ce combat

pacifique, c'est la maison Philippe H. HERZ neveu; c'est à elle qu'a

été décernée la grande médaille d'or pour la perfection de ses

instruments.

On pourrait croire qu'elle

allait se reposer sur un pareil succès : il n'en est rien;

comprenant que c'est principalement la catégorie des pianos à queue

qui intéresse l'art musical, et que si peu de facteurs en Europe

osent aborder, à cause des difficultés de fabrication qu'elle oppose

aux novateurs les plus courageux, M. Philippe H. HERZ s'est livré à

de nouvelles recherches et à de nouvelles études.

Il a trouvé un système

entièrement neuf; et, sur des données inéprouvées jusqu'à ce jour,

il est parvenu à donner aux pianos à queue des qualités que ni

l'Amérique, ni l'Angleterre, ni la France n'avaient crues possibles.

Du reste, cet habile facteur

est à la veille de soumettre au jugement de l'opinion un de ces

instruments récemment sortis de sa fabrique. Il convoque, en effet,

le public et les artistes à une soirée qui doit avoir lieu, demain

lundi, dans ses salons de la rue Scribe; là, on pourra juger de

l'importance et de la grandeur de la découverte que nous annonçons."

Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, Volume 37,

16/01/1870, p. 21

Nous devons insister tout particulièrement sur un fait qui intéresse au plus haut degré le développement de la facture des pianos en France. — C'est la première fois, en effet, qu'un simple ouvrier dans cette industrie reçoit une distinction honorifique qui n'avait été jusqu'à présent accordée qu'aux chefs de maison. Combien y en a-t-il parmi ces derniers qui auraient eu assez de désintéressement pour mettre au premier plan leur collaborateur modeste qui, sans cette initiative, serait resté éternellement obscur, pour ne pas dire inconnu ? M. Philippe HERZ aura eu cet honneur de s'être effacé sans hésitation quand son mérite personnel lui permettait de se mettre le premier en ligne. Il s'est cru sans doute suffisamment récompensé, pour le moment, parla médaille d'or qu'il a remportée d'une manière si éclatante à la dernière grande Exposition de 1867." Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, Volume 37, 08/05/1870, p. 150

L'Empereur ayant bien voulu

accueillir favorablement cette demande, une députation des ouvriers

a eu l'honneur d'être présentée par le Ministre des beaux-arts à Sa

Majesté et de lui exprimer, par l'organe de leur patron, leur

profonde reconnaissance et leur entier dévouement.

L'Empereur, avec son

affabilité habituelle, s'est entretenu, avec la députation de la

fabrication des pianos, de l'importance de cette industrie, et a

exprimé toute la satisfaction qu'il avait éprouvée d'accorder la

croix de la Légion d'honneur à M. Knust, et à tenir compte du mérite

partout où il se rencontrait.

Nos informations

personnelles nous permettent d'ajouter quelques détails intéressants

à la note du Journal officiel sur cette réception.

L'Empereur a voulu donner à

son audience une certaine solennité à laquelle était loin de

s'attendre la députation. En effet, c'est dans une des salles de

gala qu'elle a eu lieu, et, dès son entrée, l'air affable de Sa

Majesté, un mot aimable dit à chacun de ceux qu'il recevait, les a

promptement mis à leur aise.

M. Philippe HERZ a

respectueusement remercié l'Empereur, au nom de ses ouvriers, et lui

a exprimé combien « ils étaient pénétrès de l'infinie bienveillance

avec laquelle le souverain avait daigné, au milieu même de ses

plus hautes préoccupations, arrêter son attention sur un

simple artisan, récompenser et glorifier son mérite. »

Sa Majesté a répondu, «

qu'elle avait été heureuse de donner ce témoignage de sa

satisfaction à celui qui avait su contribuer, par son habileté

et son travail, au progrès de la facture des pianos. Après

quoi l'Empereur a adressé à M. Philippe HERZ diverses questions sur

sa fabrication et sur l'importance de ses produits.

La députation s'est retirée

vivement impressionnée de cet accueil, dont elle gardera longtemps

le souvenir et au sujet duquel M. HERZ reçoit de toutes parts des

félicitations."

Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, Volume 37,

28/05/1870, p. 173

Ces produits lui

font le plus grand honneur et attestent une fois de plus que la grande

médaille qu'elle a obtenue à l'Exposition universelle de 1867, tout en

l'élevant au premier rang, n'a été pour elle qu'un encouragement à de

nouveaux progrès."

Le Figaro,

26/08/1875 (gallica.bnf.fr)

4.

STREICHER

Par considération pourl'anciennetédel'établissementde M. STREICHER, etne voulant pas porter atteinte à ses affaires, le Jury décerna une médaille à ce facteur; toutefois, ce fut plutôt comme souvenir de ses anciens succès que comme récompense pour son piano. Il est vraisemblable que M. STREICHER lui-même se jugea alors avec sévérité, et qu'il fit des études comparatives des grands instruments qui se trouvaient à l'Exposition. Les pianos de MM. STEINWAY fixèrent vraisemblablement son attention plus que les autres, puisque, renonçant tout à coup aux principes de son ancienne facture, il a adopté les dispositions américaines des cordes croisées. La transformation est complète et les résultats sont heureux, car le grand piano de M. STREICHER, placé à l'Exposition actuelle, est un très-bon instrument." Exposition universelle de 1867: Rapports du jury international, Volume 2, 1868, p. 255-262

Am bewunderungswürdigsten ist der Bass, die schwache Seite so manches schönen Instruments, durchaus klar und bestimmt, jeder Ton majorenn. Das STEINWAY'sche System der gekreuzten Saiten ist in diesem Flügel angewendet; dass es die Vortrefflichkeit des letzteren erkläre, können wir aber nicht behaupten, da wir in neuester Zeit geradsaitige Claviere von STREICHER gesehen, die seinem Ausstellungs-Instrumente an Ton kaum nachstanden. Aber eine andere wichtige Verbesserung, die STREICHER allein angehört, hat den wesentlichsten Einfluss auf die Schönheit und Klarheit des Discants geübt: der elastische Hammerstuhl. STREICHER durchschneidet die sogenannte Hammerbank der Länge nach, und zwar vom höchsten Discant herab bis zum in der Mitte ihrer Höhe, wodurch die obere Hälfte, nur an beiden Enden auf einem Lcderlappen aufruhend, frei schwebt. Durch dies ebenso einfache als sinnreiche Mittel wird das bei Clavieren englischer Construction so häufige, störende Pochen des Hammerschlags im Discant beseitigt und die höchsten Töne erscheinen ganz so klar, wie beim Wiener Mechanismus, in welchem die Hammerstiele bekanntlich an keinem Hammerstuhl, sondern unmittelbar auf den Tasten befestigt sind. Nach der Tiefe zu, wo die Saiten länger und stärker klingen, vermindert sich natürlich im gleichen Masse jene störende Rückwirkung des Hammerstuhles; desshalb hat STREICHER seinen elastischen Hammerstuhl auch nur im Discant angebracht. Zugleich hat STREICHER's Mechanik durch die Anwendung der, von Fr. Ehrbar bereits in London (1862) ausgestellten Repctitionsfedern eine weitere Verbesserung erfahren, welche sein Instrument rücksichtlich der Repctition neben die vorzüglichsten französischen stellt. Neben STREICHER's Musterflügel stand, ebenbürtig an Werth, wenn auch verschieden im Charakter, ein Piano von Ehrbar in Wien. Man kennt den edlen, weittragenden Gesang, der die Instrumente dieses Meisters auszeichnet; sein in Paris ausgestellter Flügel steht an ausgesprochener Individualität der Klangfarbe obenan. Diese Klangfarbe ist nicht so glänzend wie bei STREICHER, dessen Ton auch „eher da ist", aber an Adel und gleichmässiger, charaktervoller Weichheit ist sie einzig. Der leichte Schleier, der auf dem Tone des Ehrbar'schen Flügels ruht, gibt ihm einen eigenthümlichen Reiz, welcher an den analogen Charakter der Stimme Jenny Lind's erinnern kann. Technisch liegt die Erklärung wohl zumeist in der von Ehrbar beibehaltenen feinen Belederung der Hammerköpfe, während STREICHER starke Filzlagen anwendet, welche allerdings den Ton heller und rascher auswerfen machen." Bericht über die Welt-Ausstellung zu Paris im Jahre 1867, p. 21-22

BROADWOOD

It is indubitable that there is no finer instrument in the Exhibition, and it is a question whether there be any one so fine. The price of this instrument is 200 guineas; its neighbours, however, cased in more costly woods, are valued at double that sum. Messrs. Broadwood have also sent oblique instruments which may be highly commended." Reports on the Paris Universal Exhibition, 1867, Volume 2, p. 199

Five Grand Pianofortes with Iron Frame, Patent Screw Pin Piece, and all recent improvements. Cinq Pianos à Queue, à Charpente en Fer, Plaque brevetée à Chevilles à vis, et munis de tout les Perfectionnements les plus recents. Fünf Fliigel mit eisernem Rahmen, patentirter Schraubenstimmnagelplatte und alien neuesten Verbesserungen.

No. 19,957.

No. 20,009. -----

No. 20,004.

No. 20,009. ----

No. 19,957.

| ||||||